This is an open letter to my friend Jon Trott addressing an article he wrote, A Heart Cry for a Skeptical Friend on his blog.

Dear Jon,

It would be presumptuous of me to assume your post had anything to do with me at all but for the fact that I had just a day or two before posted an essay on my recent views on the Christian faith, that you and I have had many back and forth communications about it, and because the text to your post had briefly shown up in a thread that had linked to my article. I assume I am that friend. You also asked a question at the end of your essay that deserves an answer. I hope then that you will not mind the format and method of delivery of this letter. I understand your article is about your heart and process, not mine, as my post was about my process, not yours. My purpose is to continue our dialogue, deepen our understanding if possible, and ask some questions.

Let’s start with this one. How is it so easy to leave one’s lifelong faith? Where is the comfort in leaving you speak of? I cannot use the language you did that would make that a personal offense to Jesus, because as sweet and emotionally loaded as the imagery might be, to assume Jesus is somehow humiliated or injured by the decision not to believe simply begs the question. I’m guessing he can control the damage of my questions and knows that I mean no offense to him, you, or anyone else. I could provide testimony on my own behalf on the depths to which my childhood faith permeated and defined my life and career, my songs, my mission to help others, the way I raised my own kids, and my structured commitment to my own personal growth, as painful as that was over many years, but not here. I will not defend myself against the baseless idea that the adoption and practice of my faith was flippant and the abandonment of certain doctrines little more than convenient. More on that shortly.

It is true that I am very happy to have my Sundays back, especially the mornings. I no longer feel any pressure to make excuses for, or to try to reconcile the irreconcilable. I do not worry about cosmic thought police or conjure up a mental defense for any specific action, motive, or temptation, acted on or not. I don’t worry about where the fine line between temptation and “sin” lies in any given circumstance. I no longer worry about how to conduct myself relative to a self-proclaimed authoritative first-century moral code that has little bearing on modern life, or searching for the biblical mindset on ethical and moral issues they could not have even imagined back then. Trying to do so only multiplies ecumenical divisions and disagreements. Nor do I any longer have to struggle over how my own practical and moral choices including my voting preferences, would stack up against those manuscripts as if someone was watching and keeping score, pleased by my compliance. In all these ways and more I am at peace with myself, more connected to others, I am more alive and mindful than before. I have less worry and fear. Things make much more sense overall because I now have different standards and evaluate claims by more sound methodologies, following good evidence wherever it leads, and staying open when it’s murky rather than starting with preconceived conclusions based on appeals to authority that then color the evidence. In all these ways my life is much more comfortable, easier, lighter. You’ve got me there.

Somehow I suspect that is not what you mean. Somehow I suspect that you refer to comfort and ease in a more existential way, as a way to escape what you suggest is the inherent suffering in Christianity. Where is this unique suffering you speak of? The days of lion’s dens are over in the civilized world where people are free to practice their faiths within accepted folkways and mores. It’s true that Christians and practitioners of all faiths all over the world are persecuted and killed for the practice of their faith, but since you personalize this suffering, I assume you do not mean any of this either. What on earth could you possibly mean? Is there some other kind of moral or existential persecution that, say, the members of Code Pink or Act Up do not also suffer?

Do Christians suffer over their moral choices any more than people of other belief systems? Is there some higher calling to fulfill that those of different faiths do not have? Do believers fancy themselves more graceful, more loving, more forgiving, more generous, more altruistic, more likely to give their lives for another, even potentially? The things you love about the man Jesus were unique to a purity tradition like Judaism in first-century Palestine, but are not unique to, nor were they born with Christianity. All the virtues, the teachings, all the breaking down of social barriers, acceptance, forgiveness, social justice, healing and reconciliation, unconditional love (along with a good deal of other stuff) are certainly found in the revolutionary Christ. These are human virtues, not Christian virtues, mistakenly assimilated as virtues peculiar to Christianity by its adherents in what seems to me a stunning case of ethnocentrism, ignoring the experience of the majority of the world’s population. Or is it the mere identification with the man crucified as a criminal, this most lowly God of all Gods, but who now, on the other side of the equation sits at the right hand of God and will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead? What cross is it that only Christians have to bear that somehow the rest of humanity does not, especially when virtually nobody since St. Francis obeys, much less gives any appreciable lip service to his direct, absolute commandments regarding how his followers are to live, and by this I mean practically, not theoretically?

Let me suggest a different point of view about comfort and suffering. Perhaps Erich Fromm was right when he defined freedom as the independent actions of human beings in the face of authority (his first example of which was Adam and Eve). He promoted the use of reason to establish moral values over adhering to authoritarian values. We either embrace or try to escape this freedom and its existential gnawing, of feeling separate from nature, naked, but still part of it, by any of; 1) changing oneself in conformance to a socially preferred ideal self, losing one’s true self in the process; 2) giving control of oneself over to another; or 3), destructiveness. This all sounds too familiar to me. Under this model, comfort comes not from leaving, but rather from joining, not from independence but by conformity, from being subsumed, by joining ourselves to something larger than ourselves. Resistance is futile as they say, or as you said, “there is no hope in any other.” Well, there may be and there may not be but I am not simply taking anyone’s word for it. It will have to be earned.

What existential comfort does skepticism have to offer in the face of all this? Isn’t it Christian orthodoxy that promises eternal life, a Blessed Hope, being reunited with the other faithful and the heavenly host in eternal bliss, forgiveness of sins, triumph of life over death, a sure moral code, easy answers to all our larger questions, peace that passes all understanding, living waters that will forever satiate our thirst, rest for our souls, an apocalyptic balancing of the ledgers, a triumph of right over all that is wrong? What fool would turn all that down? It would either be for lack of awareness, understanding, or more likely doubt that the claims themselves have merit. That is the real question in my mind, not whether or not I will love Jesus. No, skeptics have as you correctly implied a potential and absolute void of that ultimate meaning, no comfort per se. It is anything but easy to challenge one’s own religious heritage and lineage, one’s culture, the foundations of one’s nuclear family, especially when one is on public record, not just in the context of statements made via pop culture, but especially when that public record has been tied so closely through so many media over so many years to the sincerity and genuineness of being, to one’s dignity as a human being on a journey to know truth and commit to the highest forms of love. If there is comfort, it is in fidelity to those commitments.

Our ongoing discourse of meaning continues to baffle me. First, there is the obvious problem that just because anyone finds the idea of meaninglessness and nature’s indifference towards us (which it is by any appearance) depressing or untenable does not mean there must be an ultimate meaning, no matter how many times it is said or how vehemently. It simply does not follow. To me, ultimate meaning is not even a very desirable position. Many believers seem to argue for objective meaning, something imposed on us externally, presumably by God, a God-shaped vacuum or hole in our hearts and our very existence. What does all of that say about our freedom, “true freedom” as you once wrote to me, about choice, the freedom to choose our God, when a sense of purpose is imposed on us from outside ourselves? My own sense of meaning comes from within, from my own life, my own values, work and love.

Viktor Frankl and his work in Man’s Search for Meaning must enter into the discussion. He is favorable towards religion, and agrees that most people who survived the concentration camps also had even deeper religious belief afterwards (although presumably non-Christian), but nowhere does he suggest that religion is required for meaning. In fact he notes that the survivors’ belief is in spite of, rather than a result of their captivity and suffering. Nor does he ever talk about ultimate meaning as something set apart from individual meaning and the individual acts of a person’s life based on his or her values. Frankl was also fond of Nietzsche, but he was no fan of nihilism, believing in “…immunizing the trainee against nihilism rather than inoculating him with the cynicism that is a defense mechanism against their own nihilism.” There are, he suggests;

“…three main avenues on which one arrives at meaning in life. The first is by creating a work or by doing a deed. The second is by experiencing something or encountering someone; in other words, meaning can be found not only in work but also in love… the third avenue to meaning in life: even the helpless victim in a hopeless situation facing a fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, and by so doing, change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into a triumph.”

Even allowing for “traces of transcendence” in humanity, nowhere does he appeal to God for a sense of meaning in the face of the “tragic triad” of pain, guilt and death;

“To be sure, people tend to see only the stubble fields of transitoriness but overlook and forget the full granaries of the past into which they have brought the harvest of their lives: the deeds done, the loves loved, and last but not least, the sufferings they have gone through with courage and dignity… In view of the possibility of finding meaning in suffering, life’s meaning is an unconditional one, at least potentially. That unconditional meaning, however, is paralleled by the unconditional values of each and every person.”

"Everything can be taken from a man or a woman but one thing: the last of human freedoms to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way."

All this is fine and well, and probably unconvincing to anyone who by their own sense of values thinks that belief in God depends at least somewhat on the idea that meaning itself (and morality) must come from God. Such people will not understand those who claim that meaning comes from the individual’s own life, his own values, her own work, love, and personal triumphs. There are many, many people who have such meaningful lives with no God-ideal, which should be enough to settle the matter right there. Any plate-smashing and joint-savaging that might arise from an absence of objective meaning then, says more to me about an incomplete or misdirected quest for meaning than the requirement that meaning come from outside ourselves, that absolute death somehow makes everything meaningless. Death is not the end of all music, of all art, all science, all philosophy. It is only the end of our own. How much more meaningful then is our work today, our love today? That is all we have, and that strikes me as urgent. Frankl again; “The salvation of man is through love and in love.” You find that uniquely in your God. Others find it in other places. Some don’t find it at all.

All cultures struggle to understand the world and the meaning of life and create rich mythologies to explain things beyond their grasp. Many myths and stories are beautiful and powerful, sophisticated, nuanced and detailed. I don’t think Christianity is entirely mythological, although I believe a chunk of it is. The biblical account of Exodus is to Israel what the story of Romulus and Remus is to Rome; useful for the nation and there for a reason, but mythical. The early letters and writings of the church, apocryphal Gospels, Acts and Epistles at least, are frequently over the top in their heroic and legendary tales of the apostles and important events, but this is not the hill I want to do battle on today. I bring it up to contrast one kind of intellectual pursuit; the subjective, interpretive, archetypal, the philosophical and theological, the mythological, rich as all that might be with another, the scientific method. I want to emphasize that I consider both extremely important, but the one seems a convenient place to spend time when there is fear or ignorance of the other allowing the fearful to then fancy themselves having thought things through with a modicum of intellectual rigor. Consider the national debates on things like evolution. I commend any evangelical who at least lives in a balanced and honest intellectual world and who has taken their thinking right up to a precipice and who can go no farther before taking their leap of faith if take it they must.

I do want to be clear on this. My questions on the merits of the objective claims of Christianity will not be settled by Fromm, Frankl or Freud, not by Kierkegaard or Kant, not by Nietzsche or Dostoevsky, not C.S. Lewis or Pascal, not by Tozer, Chambers, Spurgeon or Piper, not by Billy Graham, Rob Bell or Rick Warren, N.T. Wright, or W.L. Craig. Many of them are scholars and brilliant thinkers, but they cannot bring much to bear on those claims, even if they do help interpret them or add dimension and meaning. Let’s dispense with all this for now, the philosophies and propositions that can go this way or that. For me it is all superseded by the searing daylight of the large and growing body of scientific truth. My belief in any claim of any nature is rightly held in proportion to the empirical evidence for its support. It is not perfect or complete, but science is demonstrably the best way we can know anything objectively, the only tangible, testable and replicable thing we have at our disposal to solve our problems, help us survive and take us into the future.

"All of our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike -- and yet it is the most precious thing we have." - Albert Einstein

I am interested in what really happened because I think it matters for us all today. Once I have an idea or a sense of what happened or not, then my questions can turn more towards what it means, what to do about it and putting it all into some kind of meaningful context or perspective. The answers I am interested in will be settled by the scientists of many disciplines, much as many hate or fear the idea activating all kinds of logical fallacies in opposition. They will be settled by the atheist and the theist academy, I don’t care which, as long as the results are independent and peer-reviewed. Yes, it’s a nice story that liberally and generously uses natural claims to make its case. I want to see what kind of teeth it has. If it’s mostly a story, even if in parts it’s a beautiful and moving, sophisticated and nuanced story to help us come to terms with our humanity and our world and help us deal with ideas so terribly awful because of their indifference towards us (some rule out the possibility of terrible ideas simply because they’re terrible!), then I want to learn what I can about my own condition and how I can best love.

Finally, our questions for each other. Will I love Jesus, you ask? The gentle and humble-of-heart Jesus who broke down social and purity barriers is easy to love. What do you mean by love though? Do you mean to ask if I feel drawn to him, and take his heart to heart? Yes, I can assent to that. I suspect that is not what you mean. I suspect that by “love” you mean a love that would result in the picking up of a cross and following him (whatever, again, that cross-bearing thing actually means). I cannot do that. Why? Because besides the questionable merit of the claims, the gentle and humble-of-heart Jesus also had plenty to say about sin and eternal torment, the axe already at the root, a lake of fire where the worm dieth not. Now perhaps Jesus said that stuff or perhaps he didn’t, perhaps he meant something else, perhaps it was figurative. There are arguments on all sides, but cutting through that and taking these at their orthodox meaning, there is nothing in my conscience or mind that allows me to assent to such a pernicious and foul teaching from an all-loving deity. Keith Parsons suggests, and I agree, that “Two doctrines of orthodox Christianity make sure that it will always be intolerant in spirit if not in practice: (a) exclusivism, and (b) the doctrine of hell.” Intolerance must never be tolerated, much less followed. I am in one sense a proud heretic, in another, agnostic. Thankfully Jesus would welcome me at his table. I would accept and invite him to mine as well. That’s the best answer I can give you.

I will then ask my own. You mentioned that my writings outlining my journey away from evangelicalism and into the daylight of doubt were “self-confident,” that perhaps expected or required “atheist-busting syllogisms.” Do you mean this at all pejoratively? Am I any more self-confident in my writings than you are when you write, “I know I met Christ. You do not know that,” or “If I am not a liar, then Jesus is true?” Or is it the case that only Christians can be self-confident? Are self-confident heretics, agnostics, or atheists in a class with uppity persons of color or outspoken assertive females, fine as long as they know their place? There is no framework in Christian orthodoxy for treating people who have lost or suspended their faith with dignity and equality, those genuinely asking legitimate questions, trying their best to navigate the maze of suffering and elusive meaning in every human life. They are considered backslidden, rebellious, hard-hearted, in error, blind, apostate, sinful, in all kinds of language, less-than. Their faith must not have been genuine, it must have been shallow, of dubious and weak commitment, insincere, fraudulent, perhaps for illicit gain. “They went out from us, but they did not really belong to us. For if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us; but their going showed that none of them belonged to us.” I get comments like these all the time. One Christian even feigned vomiting on the thread under which my essay was posted. None of the many Christians participating called him out.

This seems to me an obvious example of the other inherently intolerant Christian doctrine to which Parsons refers; exclusivism. All who come to God must do so through Jesus Christ, apparently. Of course there are other ways to read that as many non-literalist, non-fundamentalists do, but there is no way to retain orthodoxy doing so. Historically confessions were extracted under pain of death and there is still no chance for a professed skeptic to hold high office in this country. In earlier times I’d have been arrested, maybe worse for even writing all this. My intention is to give people the benefit of the doubt. Few would admit to intolerance, although Christians do use their own version of “separate, but equal” in the equally evil “hate the sin, love the sinner.” Is there room at your inn for those with sincere doubt or will correct belief, orthodoxy trump love? Is it at all possible that God Is Not A Christian, and that that revolutionary idea would not be at all offensive to Jesus because it more closely captures his heart than the exclusivity of evangelicalism? Will you renounce exclusivity and the rhetoric that goes with it? Will you acknowledge unequivocally the equal legitimacy of sincere inquiry and question, of skepticism, of journeys like mine, even if you disagree with the outcome and conclusions? Will you acknowledge the fulness of the human experience outside evangelicalism, outside Christianity and outside faith altogether? While there’s still the issue of hell to deal with, this is the only Jesus I could ever consider loving.

Thank you, dear friend.

P.S. – Perhaps you would also consider extending legitimacy to my work by naming me when referring to my writing, an appropriate and customary practice, linking to the article too so people could evaluate it first-hand. That would be great.

WORKS CITED

Frankl, Viktor E. (1984). Man’s Search For Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. New York: Simon & Schuster

Fromm, Erich (1969). Escape From Freedom. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

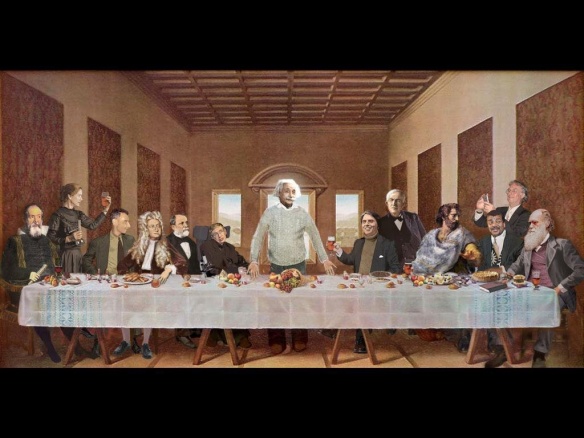

Photograph (Left to Right): Galileo Galilei, Marie Curie, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Isaac Newton, Louis Pasteur, Stephen Hawking, Albert Einstein, Carl Sagan, Thomas Edison, Aristotle, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Richard Dawkins and Charles Darwin. Some regrettable omissions, especially James Maxwell and Francis Collins, and some questionable inclusions, but you get the idea.

Thanks to Susan Ann Luce for proofreading and editorial advice.

I am troubled that people think the questioning and even walking away from Christianity is somehow…easy. It would be far easier to keep quiet and go through the motions. To nod and pretend to believe.

I stumbled upon some people discussing Ojo’s blog and found myself amazed at the graceless assumptions so many self avowed Christians were able to make. People look at you differently when you confess you unsure you believe in Christianity. They treat you differently. They become incredibly comfortable making proclamations about why you no longer believe and your sincerity when you did.

I blame G.K. Chesterton and his line about the Christian ideal being found hard.

Thank you for sharing these thoughts – if I believed in fate, I’d say it led me to this post! 😉

I am only somewhat “out” as agnostic, having been raised a Christian and so truly believed for many years. I think my family knows, but we don’t talk about it – they are strong believers, and I 100% respect that, and it appears that they respect (or simply ignore) my decision in return. I don’t talk about the fact that I’m no longer a Christian, because A] though my transition was about a year ago, that doesn’t trump 22 years of Christian raising & belief. It’s very recent in my heart. B] At times, I still want to believe – I struggle sometimes, because what I know in my head and feel in my heart sometimes conflict. My heart will occasionally cry for something more because I am used to it, and my head reminds me that something more isn’t going to be there unless I create it. I am fulfilled by nature, love, family, and friends – I don’t need a god to fill that hole. Still I hesitate, because I fear I would receive much more criticism and “persecution” for my lack of belief now than I did when I was a “Bible thumper” (which only occurred once as a Christian).

I too am glad to have Sundays back without feeling guilty. It took over 2 years for me to “realize” that I was agnostic – I had stopped feeling guilty about going to church long before, but still clawed in vain at the religion I desperately wanted to believe in, but knew better. I don’t think I’m any better or worse than others – I still respect those who choose to believe in Jesus Christ, because it is their choice to do so. Like you said… we would all be welcome at his table. Thanks again for sharing.

Pingback: It’s Different, Because I’m Right! « In One Ear…

Hello,

Found this blog while reading some stuff online about the band “The Choir, which lead me to reading about Undercover, which in turn lead me here. I was once a big fan of Undercover, in the early 90s and until very recently hadn’t listened to your music in years. I recently have gotten ahold of those early 90s albums again and look forward to relistening to them. I am intrigued by your journey, as I have also been on a journey for most of my life that began in the fields of very conservative evangelicalism, though, for now at least, I am headed in a different direction than you are.

I am really intrigued by your claim that “intolerance must never be tolerated.” On what basis do you make such a claim? It doesn’t seem to me that is a self-evident claim, and it even seems to me that the claim as you have stated it is self-contrdictory. To not tolerate intolerance is to be intolerant of something. It may be a different something than those you take issue with, but it is still intolerance of something. Therefore, I don’t see how it can escape censure by it’s own standard.

Ojo,

First, I have to thank you for your transparency throughout many of your blog posts. It is something that “christianity” (small “C” intentional) has lacked for far too long. The unfortunate thing is that lack of transparency and heir of perfection has prevented many people from being able to put their faith in Christ. Even more, it has driven many who did, at one time, believe in Christ, away from Him. I won’t pretend to know what lies within your heart when it came to you walking away from christianity, nor will I try to enter in to an intellectual debate with you. I don’t have the intellect to do it anyway! I haven’t read all of your blog posts, and honestly, have only scanned over some of them. As I scanned your response to Jon though, I had the thought, “Ojo is finally at the place where he could actually experience Christ!” You have stripped away all notions of religion. You have been freed of all the trappings and stupid rules that christian society imposes on people. You are free to meet Jesus for who He really is. It is exactly what I’ve been seeking since the death of my 3 year old son, nearly 2 1/2 years ago. Up until then, I was perfectly content with christianity as usual. When my son got sick, it brought everything I had ever learned in to question. It challenged my faith and caused me to seek out truth for myself. Having been brought up “in the church,” I am now on a quest to strip away all of the things that I have been taught that are rooted purely in religion. I have not lost my belief in God. In fact, since my son died, my belief in God is growing as I’ve seen how He has shown Himself over the past few years. Some may see the evidence and say, “well, that’s just a coincidence,” but the evidence, to me, is indisputable.

I have no words of wisdom for you. I just wanted to share my perspective. In my eyes, you have been given a gift. One that has been incredibly freeing to you. One that I hope I receive, as well.

Kevin

This is very interesting-on both sides. Im curious, however. I see a great many works, philosophers and other sources cited but nothing biblical. Over the last 24 hours, Ive read quite a few of the blogs on here, Joe, but I still disagree with the points of view in a number of them, well, nearly all of them to be honest. Im sorry my initial posts came off as harsh, but the essence of what I was asking, and still am asking, remains. I read your blog regarding your conversion back in the 70s and I saw that you were searching, which is good. One curious thing I did notice was that, even though you were seeking counsel from godly people, which I think is a good thing, I saw no mention of daily personal Bible reading and study along with prayer. Maybe I missed that or it wasnt included in the article, I dont know. Just thought Id mention it.

Thank you for reading, even if you disagree. I am here to document and chronicle my own journey, to speak my own truth, not to build a consensus or to try to convince anyone of anything. That may or may not happen, but is is incidental. The reason there is nothing biblical in this post is because Jon raised specific questions related to specific writers and the bible doesn’t really have any bearing on that.

I am not inclined to make my personal routines, whatever they are, public in general so it is not remarkable that I did not make any mention of those things. But the implication, at least the question you raise is whether I actually did those things or not, which somehow would have a bearing on the legitimacy of my faith. The question then assumes bad faith.

Finally, you referred to a question you were asking and are still asking and I’m not sure I know what that question is. If you have one and can ask it in sincerity and respect I am happy to answer. ~J